Friendly fire in the North Pacific

Friendly fire is an attack by a military force on non-enemy, own, allied or neutral, forces while attempting to attack the enemy, either by misidentifying the target as hostile, or due to errors or inaccuracy. Fire not intended to attack the enemy, such as negligent discharge and deliberate firing on one’s own troops for disciplinary reasons, is not called friendly fire. Nor is unintentional harm to non-combatants or structures, which is sometimes referred to as collateral damage. Training accidents and bloodless incidents also do not qualify as friendly fire in terms of casualty reporting.

Use of the term “friendly” in a military context for allied personnel or materiel dates from the First World War, often for shells falling short. The term friendly fire was originally adopted by the United States military. Many North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) militaries refer to these incidents as blue on blue, which derives from military exercises where NATO forces were identified by blue pennants and units representing Warsaw Pact forces by orange pennants. Whereas in classical forms of warfare, including hand-to-hand combat death from a “friendly” was rare, in industrialized warfare, deaths from friendly fire are common. (Wikipedia)

The war in the Northern Pacific theatre was not an exception.

7 June 1942

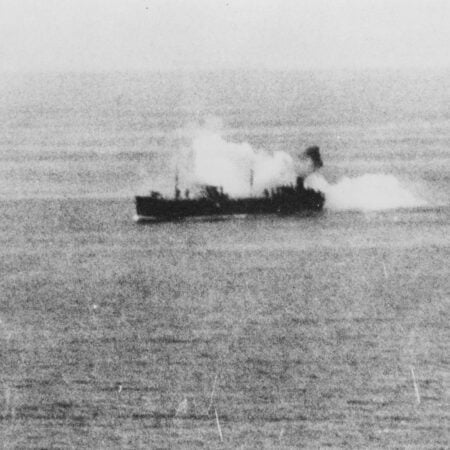

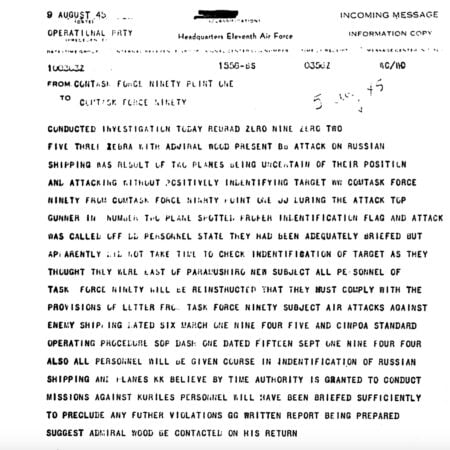

Soviet freighter SS Djurma went under aerial attack in the vicinity of Dutch Harbor. The ship, loaded with 10 tons of explosives and detonators, was en route from Seattle to Vladivostok. On 3 Jun, the captain received a radiogram from Dutch Harbor about the Japanese bombing with a warning to all ships not to enter the port. On the morning of 7 Jun, the captain requested permission to enter Dutch Harbor, which was granted by the Navy authorities. However, within 20 miles of the port, the unarmed ship was attacked by the formation of P-38s of the 54th Fighter Squadron, which repeatedly strafed the deck and structures. (The Soviet flag was hoisted on the mast and painted on the sides). After the fighters disappeared, the formation of 5 bombers flew over and signaled the ship to stop. The port authorities were notified on the radio about the incident, and the USN corvette soon arrived and collected wounded sailors.

Below is the quote from the letter of Maj. Gen. William Butler, Commander, Eleventh Air Force to Gen. Henry Arnold, Chief of Staff, U.S. Army Air Forces, 16 Jun 1942

“The (P-38s) flight (of the 54th Fighter squadron) ordered to Otter Point on Umnak Island, accidentally strafed Russian freighter, thinking its flag was Japanese. Fortunately, no one was injured. One of the pilots on landing at Otter Point forgot to safety the gun switch and depressed it on landing, sending a stream of rounds down the runway. The squadron had “been pretty wild for a couple of days and chased friend and foe alike.”

Thirteen people were injured on board the SS Djurma and many of them received treatment at Dutch Harbor Hospital. Analysis of the first photo, dated 1944, however, does not show a “clearly visible” painting of the USSR flag on the hull of the ship. Possibly, in 1942, the markings were more visible.

17 July 1942

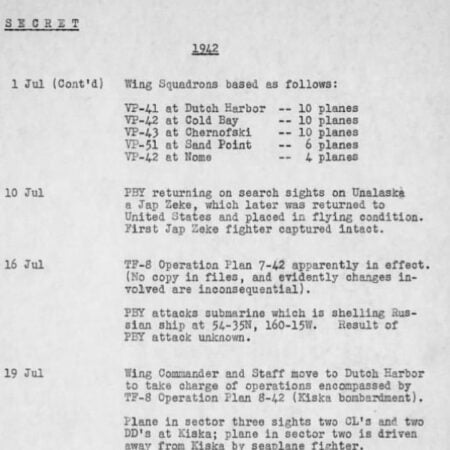

Catalina in Sector 13 (coordinates 54-35N, 160-15W) intercepted an “SOS” signal and, within five minutes, sighted a submarine shelling a Russian ship (most likely, freighter SS Uelen).

The plane attacked the submarine with depth bombs. The submarine submerged as the patrol plane approached, so the damage was unknown.

This one was an example of a truly friendly and helpful fire.

The capture of Attu in May 1943 placed Americans within flying distance of the northern Kurile Islands and the Kamchatka Peninsula.

In early June 1943, Lt Oliver Glenn from VP-61 decided to fly to Petropavlovsk. He informed his squadron commander, who, although refusing to sanction the flight officially, did give tacit approval by suggesting that a photographer be sent along.

Oliver Glenn and his crew made it to the Russian port city as planned, where, for the first time in months, they saw trees, houses, and streets. Two obsolete I-16 Mosca fighters rose to intercept them. Seeing that the Americans meant no harm, the Russian pilots flew off the wing tips of the PBY as Glenn and his crew proceeded along the coastline before turning and heading back to Attu.

The Russians apparently never complained of violating their airspace, and nothing official was said about the unauthorized flight.

Lt Cmdr Carl Amme, the commander of VP-45, also decided to try his luck with the Russians. On one flight out of Casco Cove, he passed the north side of the Komandorsky Islands, where he observed construction. The next day, he dispatched Lt. Stitzel to survey the construction site from the air. Stitzel dutifully returned with several excellent oblique and vertical photographs. When Commodore Gehres saw them, he blew his top and directed that Amme discipline Stitzel for violating Russian neutrality. Amme did not take any further action, but the episode alerted him to Gehres’ feelings about unauthorized flights; several weeks later, he was reluctant to seek official approval for a rescue effort. (John Haile Cloe, “The Aleutian Warriors”)

July 1943

The Eleventh Air Force suffered a series of embarrassments during the month. One mission of B-24s following a Fleet Air Wing radar equipped PV-1 turned back with it despite the fact that the visibility over North Head was clear. One crew from the 404th Bombardment Squadron challenged a friendly destroyer and got the wrong response. The crew learned later that they had the outdated recognition codes. Another B-24 on a weather reconnaissance attacked what it thought was a small Japanese vessel. It turned out to be a Navy PT boat. As a result, the crew was ordered to visit the PT boat crew in Constantine Harbor and apologize. (Pitt, Wide Open on Top, p. 227.)

9 July 1943

Submarine Permit (SS-178), believing her quarry to be a Japanese trawler, shells Soviet oceanographic vessel Seiner No.20 27 miles off Kaiba To. Once the mistake is realized, Permit comes alongside the blazing vessel and rescues the survivors before the Russian craft sinks. The Soviet sailors are taken to Akutan, Alaska.

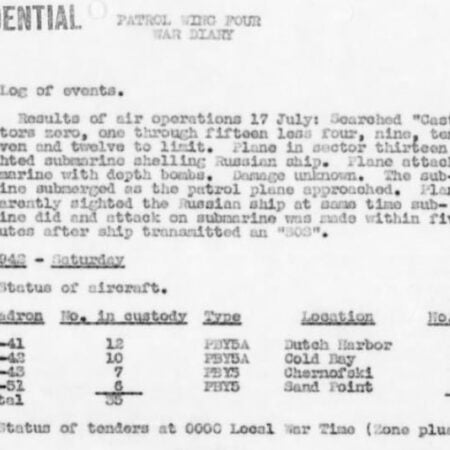

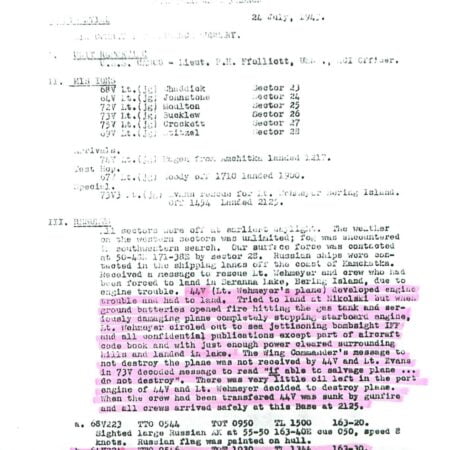

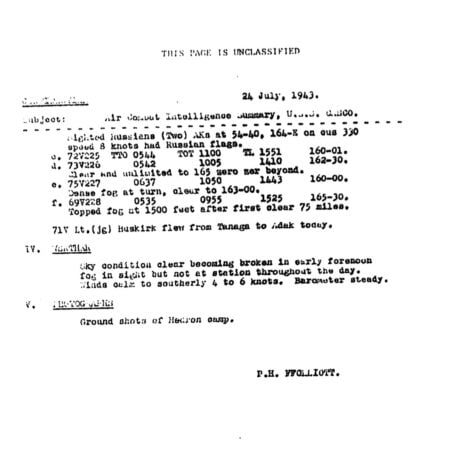

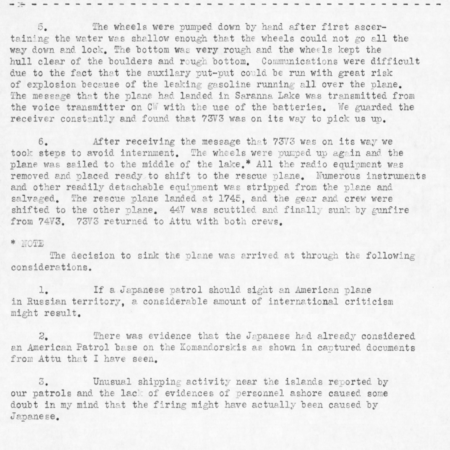

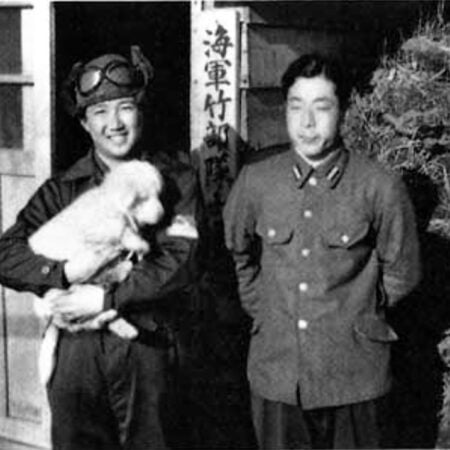

24 July: Catalina 44V BuNo 04486 of VP-61 in Fox Annex sector three, approximately 5 miles north of Nikolsky Village, Bering Island, developed port engine trouble (oil loss) which required a forced landing in Nikolsky Bay in the vicinity of the village. While attempting to land, a Russian ground position opened fire and seriously damaged the plane, stopping the starboard engine and puncturing the starboard wing tanks. (FAW4 Diary).

Lt. Wilbur J. Wehmeyer turned the PBY to the sea, where bombs and all excess gear were jettisoned. With only eight gallons of oil left, he succeeded in landing in Sarana Lake on Bering Island, a few miles inland from Nikolski Village, after radioing his position to the base. At 1454 Lt. (jg) Roy Evans from VP-45 in Catalina 73V on command by Lt Cmdr Carl Amme, departed Attu to rescue Lt Wehmeyer and crew. Amme cautioned Evans not to use his radio during the rescue operation. To further make sure that higher headquarters did not find out what was going on, Amme directed his communication officer to fake a communication outage.

This mission was successful. Evans arrived at the lake just ahead of a Russian patrol. All confidential material in 44V was jettisoned at sea before landing with the exception of a portion of the aircraft code retained and returned by the pilot. (John Haile Cloe, “The Aleutian Warriors”)

44V was sunk by gunfire from 73V, which returned to base at 2125W. Lt Wehmeyer stated he took this action to avoid international complications and because he feared the Japanese might be in possession of the island (FAW4 Diary).

Catalina 64V searching Fox Annex Twenty-four was also fired on by Russians at the Komandorski Islands. In view of these incidents, the Wing Commander Gehres warned the pilots that the Russians fire on belligerent planes and directed that they keep clear of Soviet territory.

1st October 1943 (William time zone, Aleutians)

Catalina 76V of VP-45 piloted by Lt (jg) Carpenter, made contact with fishing vessel on the high seas at Lat.54*32′ N., Long. 163* 25′ E. The vessel opened fire on the plane. The Catalina strafed it well, driving all personnel below deck and then approached close enough to observe that it was flying a flag bearing a red hammer and cickle on a white flag. After the strafing the vessel ran up an identifying flag hoist.

PBY 44V BuNo 04486 of VP-61 was shot upon from “possibly Russian” freighter at 53-08N, 177-40E. Lt Wehmeyer returned to base before the bombers arrival due to lack of fuel.

4 February 1944, “Close call”

Lt. (jg) Dryden of V-62 in PBY-5A 47V misidentified the entrance to Avacha Bay as Lopatka Strait and made his first landfall on the Cape Mayachny light at the entrance to Avacha Bay, Kamchatka, at 1145. After running south along the Kamchatka coast until 1320, he thought Cape Zhelty was his target area of Kurabu Zaki. Before dropping any explosives, however, he obtained indications of more land farther to the south. He continued on a southerly course and, at 1345, definitely identified Cape Lopatka, from where he headed for a sweep over Shimushu.

16-17 Mar 1944 Three 404th Bombardment Squadron B-24Ds flown by Lieutenants Vogler, Victor Babkiewicz and John A. Nixon, Jr., took off from Shemya between 2232 and 2400 on an armed night reconnaissance mission over Onekotan Island in the central Kuriles. Each carried a bomb load of ten M46 photoflash and six 100-pound general-purpose bombs.

Lieutenant Nixon took off at 2400 in 41-11924 “Duchess,” and made and began dropping his bombs at 0535 over what he thought was the Kurile Islands. His radio compass was not operating and he was uncertain of his position, Lieutenant Nixon was not certain where he dropped his bombs. He finished dropping his last bombs 0455 and turned east. The navigator was able to get an accurate fix on their position when they reached the northern tip of Bering Island in the Komandorskies. He computed that they might have dropped the bombs over the Kamchatka Peninsula. Lieutenant Nixon landed at 1018.

Two cases of friendly fire were documented by the Japanese.

13 May 1944 Ventura 48934/9V, piloted by Lt Hardy V. Logan Jr. of VB-135, was shot over the water near Shumshu Island by J1N-S Gekko of 203 Ku flown by CPO Yasuro Baba 馬場康邦 and WO Yoji Amari 甘利洋司 on May 13 at 21:39, Japan time. Another Gekko flown by Flight Warrant Officer Masanobu Maehara 前原眞信 and Flight Chief Petty Officer Kunizo Miyazaki 宮崎国三 did not return from the mission. Later investigation discovered the second Gekko was shot down by Japanese Army antiaircraft artillery by mistake.

From the diary of Capt. Ryutaro Yamanaka, CO, 203rd Ku:

May 13

2100: An air-raid warning was issued. There was no moon, but it was a beautiful starry night. Night fighters took off to scout.

At 2130, Searchlights captured the enemy plane. The white Lockheed looked as if it was floating quietly in the air.

I expected to see this plane going down tonight.

Suddenly, AA artillery roared, and the Ventura turned left, out of searchlight beams, and vanished in the darkness.

2135 Air raid warning ended

2150 A night fighter No.2 (Baba/ Amari) landed to reload guns. The crew reported that they shot the enemy plane down at 2139 over the sea east of Kagenoma. They took off again to continue patrol; however, no more enemy planes were found.

No.1 plane (Maehara/ Miyazaki) radioed the base at 2130, indicating that it was about to chase the enemy plane, but nothing had been heard from them since then. I ordered every unit under my command on the island to commence searching after dawn.

May 14

Fighters searched the assigned patrol area at 0330, but nothing was found. The Konkyochitai at Chishima (naval port administration HQ) also found nothing.

The Chief Staff Officer for the naval port administration HQ told me that the missing plane probably had been shot down by friendly (Army) AA fire. I thought I had to clear up this thoroughly: Army AA probably shot our boys down… which is a severe violation of the agreement between the Army and Navy. (Naval AA was silent, but Army AA fired after the Gekkos took off )

After breakfast, while contemplating in the officers’ room, the Chief Staff Officer approached me and informed me of a condition report from a naval senior aerial defense personnel.

He heard the chasing night fighter fired several test rounds, but Army AA unexpectedly started simultaneously. The fighter in the air vanished suddenly, and its roaring was not heard anymore after the AA stopped firing. Since Navy AA didn’t fire even a single shot, it confirmed that the Army shot down our fighter.

1140: Army Staff came conveying a message of condolence to Senior Staff for the 12th Air Fleet, IJN. The Army staff told the naval officers that they would never fire AA when night fighters were operating at night. Although it was not a formal apology from the Army, I (Yamanaka) suspected that the Army knew they were responsible for losing the #1 Gekko.

c.1400 An Army Staff officer made a call to express their condolence. He told us that the Army would not fire their AA anymore the next time our fighters took off for an interception. I felt the Army realized what they had done last night.

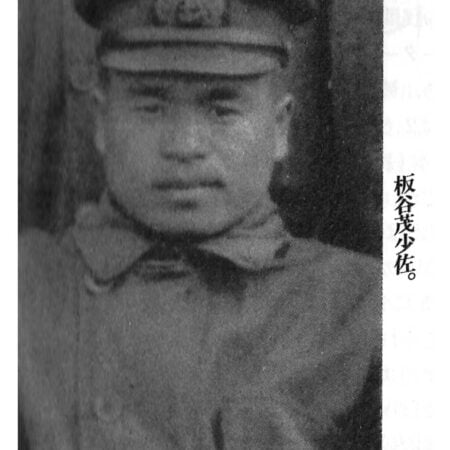

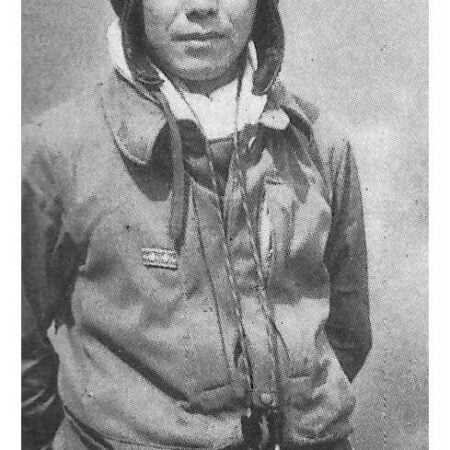

24 July 1944, Lt. Cmdr. Shigeru Itaya 板谷茂主, Chief Staff Officer of the 51st Air Flotilla, was killed in the Kuriles due to a friendly fire accident. Flying in a transport-converted Type 96 land-based attack plane (G3M “Nell”), he was mistakenly intercepted by the 54th Sentai Ki-43 fighters led by 2nd Lieutenant Hiroshi Araya 新屋弘市.

Army pilots received a radar warning of an approaching plane early in the morning. The planes on standby immediately took off. The number of planes is unclear: Mr. Araya recalls that it was one Shotai (platoon) of four aircraft, and Mr. Usui remembers that there were four to six planes. The commander was 2nd Lieutenant Araya, his wingman was Corporal Yoshijiro Ogawa 尾川芳治郎, the third plane was piloted by Sgt Major Masao Ezaki 江崎増男, and the fourth by Sgt. Major Kenjiro Usui 確井 健次郎. The youngest pilot of the group was Sergeant Ogawa, a member of the 11th Junior Pilots’ Association class who joined the 54th Squadron in October of the previous year. Although he had experience in enemy encounters, he had not yet aimed fire at them.

According to Ogawa’s recollection, Capt. Kyū Koshi-ishi, 輿石 九 and Sgt. Masao Fukuda 福田正雄 flew to the east of Shumushu Island before them, which matches his “four to six planes” theory. This can be seen as an action to cut off the path of the faster PV-1.

In the ⅝ cloudy conditions, and without information about friendly planes in the area, they mistook a Type 96 plane for an enemy PV-1 and shot it down.

At the time of his death, Lt. Cmdr. Shigeru Itaya was serving on the staff of the 51st Air Flotilla. Itaya served with the 15th Kokutai, 12th Kokutai and aboard the Ryujo during his career. He is best known for his time aboard the Akagi and as the commander of the 43 fighters that flew as air cover for the 1st wave strike force at Pearl Harbor.

The names of the crew members who were on board at the time and were killed in action were written in the squadron’s journal.

Lt. Cmdr Shigeru Itaya (Staff Officer) 板谷茂主 少佐 (席参謀)

Capt. Shigeru Yamamoto (Commander) 山本茂 大尉(指揮官)

WO Muneo Sayano (Chief Pilot) 鞘野宗夫 飛曹長(主操)

CPO Ikuo Hagiya 萩谷幾久男上飛曹

CPO Goro Matsuura 松浦吾郎上飛曹

PO1c Masao Nabeta (Scouter) 鍋田昌男一飛曹(偵察員)

PO2c Tadamasa Tsuruta 鶴田忠正二飛曹

PO2c Fusotaro Higashioka (Telegrapher)東岡房太郎二飛曹(電信員)

WO Shoyasu Miura (co-pilot) 三浦昌保飛曹長(副操)

Sergeant Major Katsutaro Marushita (onboard maintenance) 丸下勝太郎整曹長(機上整備)

There seems to be one other person, but his name is unknown.

Photo credit: Koku-Fan, February 1996, Yoji Watanabe 渡辺洋二 “The Final Interception Battle” さいはて“迎撃戦”

27 August, 1944 (William time zone, Aleutians)

Fleet Air Wing FOUR War Diary: “A 400 ft tanker heading north was attacked off Kamchatka coast, that was believed to be Onekotan To. (76V, Lt. Price). One of the incendiary bombs was observed to seen to explode on the deck of the tanker aft of amidships, starting a fire which could be seen for 30 min during departure. During the attack, Lt. Price saw what he described as a white rectangle with a red circle in the center, painted on the side of the ship, and members of the crew saw two flags flying above the superstructure which were described as “red and yellow stripes” and ” white with a red circle in the center”.

Later the tanker was found to be the Soviet SS Emba, heading from Vladivostok to the United States. An article about the incident was recently posted here. As a result of the attack, two Soviet sailors were wounded, one fatally. His body was committed to the sea in Ahomten Bay (now Russkaya Bay). The tanker remained underway and completed the passage to Portland (Oregon), where it was repaired. In Soviet historical literature, this incident was erroneously dated October 14, 1944, and the location of the attack was indicated as the First Kuril Strait.

All VPB-136 (and later- VPB-131) Venturas were equipped with five .50 caliber machine guns in the bow, three in the “chin pack” under the fuselage, and two on the top. A salvo of all five bow machine guns could easily split a smaller wooden vessel in half, making the PV-1 a formidable strafing platform. Interestingly, according to “Pat” Patteson of VB-135, the main issue with using the bow guns was the rapid buildup of cordite fumes inside the cockpit.

Identification was never a sure thing. Soviet vessels were supposed to have a big USSR painted on each side and to aid in our identification they had our challenge and reply codes. Three B-24 heavy bombers found an AKA (merchant ship) that looked like a Liberty but with no markings or flags of any kind. The aircraft challenged but got no reply. After milling around for awhile they decided to attack with .50 caliber machine guns, setting the vessel on fire. Possibly keeping in mind the stories and pictures of the Japanese beheading allied fliers, they strafed the lifeboats after these were in the water. That was not a good thing to do by any measure, but understandable. The bombers left the scene shortly so we never knew what happened to the ship or crew. In two days we had people from the State Department swarming all over us. There followed stern lectures on identification to protect our “neutral” friends(?) the Russians. We had many more slide sessions and movies of all allied and enemy warships and merchant vessels. This was a welcome break from “Ice Formation on Aircraft” and “Protect Yourself from VD”, but we couldn’t understand how studying the profiles of German and Italian warships pertained to us. One of our other squadron’s pilots damaged a Russian sub that was in the “attack everything” zone at periscope depth. Once again a hue and cry from Washington – a shrug of the shoulders from us.

(Turk Orr, VB-136 and VPB-139 pilot, from the book “How It Was, Reminiscences of a Navy Pilot in the Aleutians”)

27 September 1944

Lieutenants Moorehead and Bacak of VB-136 were confident their Venturas were off the western shore of Paramushiro when they spotted a group of ships consisting of two freighters and a trawler. None of the vessels had a flag or other identifying marks. In light of recent events and instructions to avoid attacks against neutral vessels, the crews of both aircraft circled the ships three times, examining them with binoculars and repeatedly challenging them with identification requests using Aldi lamps. There was no response from the vessels. After photographing the ships and receiving no response, Lt. Bacak made a strafing run on one of the freighters, expanding about 300 .50 cal rounds from the turret and the bow machine guns and an additional 50 .30 cal rounds from the ventral guns. The ships returned light inaccurate AA fire. The pilots also noted the explosions of anti-aircraft shells from coastal batteries. The planes, pressed by the remaining fuel, had already set course for their primary target – the airfield at Cape Kurabu (Vasilieva) on Paramushir- and had not attempted additional attacks. Curiously, both crews did not find the target: Bacak reported “bombing through a layer of clouds,” Moorehead simply jettisoned his bombs into the sea before turning to the base. Post-flight analysis of photographs showed that the actual location of the action was the western coast of Kamchatka, approximately 30 miles north of Cape Lopatka (Ozernovskiy area).

Many times our patrols encountered freighters headed for Russian ports and we were to challenge and identify them as friendly. Our crews were given a new code signal each day and a ship was to blinker back a coded reply. The first time we challenged an AK we circled and blinked six times before getting a response. Other pilots also complained about the slow or incorrect response. None of us were ever fired upon, but one crew finally fired into the water ahead of the ship and did get a correct and immediate reply. I did not hear about the bombing attack on the tanker. As we said in the Navy ‘It wasn’t on my watch’.

(Lewis “Pat” Patteson, VB-135, personal communication, 2015).

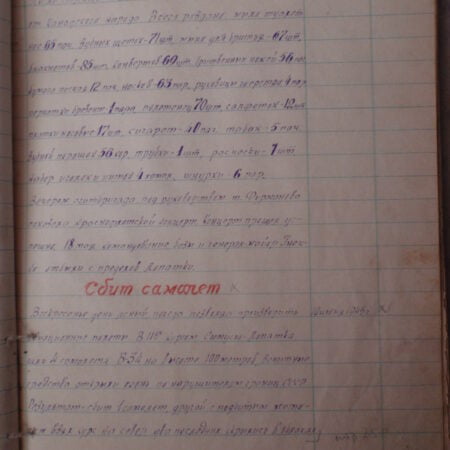

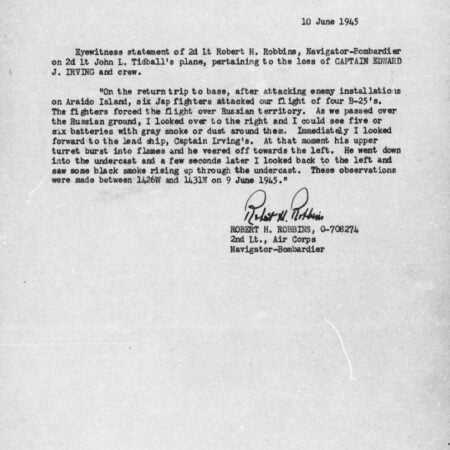

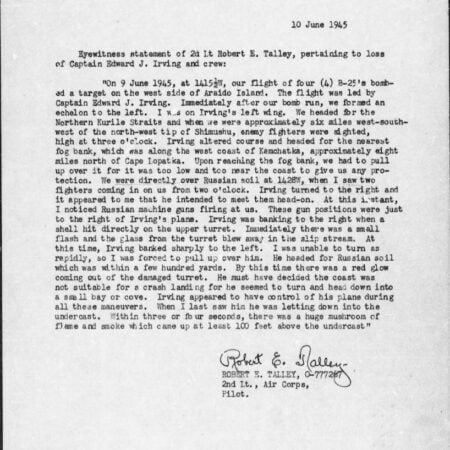

9 June, 1945 (William time zone, Aleutians)

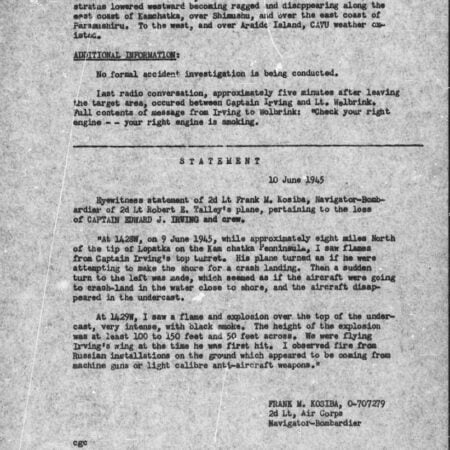

Eight B-25s of the 77th Bombardment Squadron took off from Attu toward the targets at Araido Island west of Shumushu to divert enemy attention. At the same time, the Navy Taskforce approached the southern tip of Paramushiro to shell installations. Captain Edward Irving led the first flight of four bombers. The visibility on the way to the target was so poor that the second flight almost immediately lost contact with the first. John Tidball, one of the pilots of the first flight, recalls: “We four continued ‘on the deck’ for the entire trip. I remember vividly at one point maintaining contact with Irving by watching the wake in the water by his props.” When Irwing led the flight across Cape Lopatka, Talley broke radio silence to remind Irving that “this is Russia, and we don’t do this.”

Irving responded: “Maintain radio silence and your position.”

“It was the most interesting to see the cape from sixty feet,” Talley said. It was flat-plowed ground and included one old fellow with a wooden plow and one horse. He never looked up.” Talley told his crew that there would be no firing toward the ground under any circumstances.

The four B-25s unloaded their bombs over Araido and then made a sweeping turn to head back to Attu. By that time, however, enemy fighters were swarming and chasing the flight, led by Irwing, toward the cape again. “The fighters began their attack as we were over the cape,” Talley said. A glance by Talley revealed that the plowed field he had observed “had opened up. There was a deep trench filled with men and equipment. “I was flying on Irving’s left wing,” he reported. “It was then that I believe I saw tracers from Irving’s right waist gunfire toward the ground. I have wondered if Irving ever told his crew they were crossing Russian territory. A gunner could have seen troops in that trench and automatically fired at them.”

Why did Irving intrude on Soviet territory a second time? “I can only guess, ” John Tidball said, “pressure from the Japanese fighters caused him to lead the flight over the tip of Lopatka again. At any rate, we were being shot at by the Japs from above and the Soviets from below. It was not a good place to be.” According to Talley, Irving was under 100 feet altitude when ground fire hit Irving’s bomb bay fuel tank. The explosion shattered the top gun turret, and flames erupted from the cavity. Talley said that he urgently told Irving by radio “to turn left” toward the water and thought Irving was trying to comply. Then Irving’s bomber went out of control, dived into a fog bank, crashed, and exploded.”

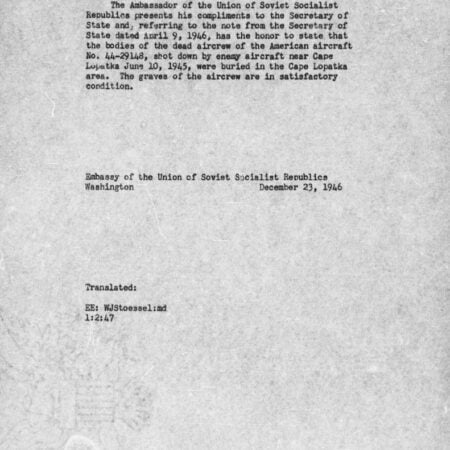

The crew members were buried close to the crash site by the Soviet soldiers. In a few days, Irving’s wallet was transferred to the head of the group of American airmen interned in Petropavlovsk. In the summer of 1949, the bodies were returned to their families in the U.S. via Petropavlovsk, Vladivostok, and Japan.

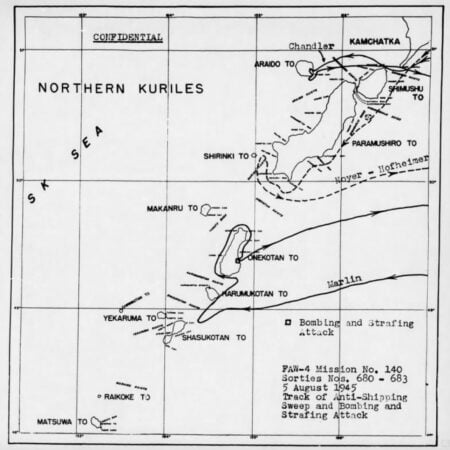

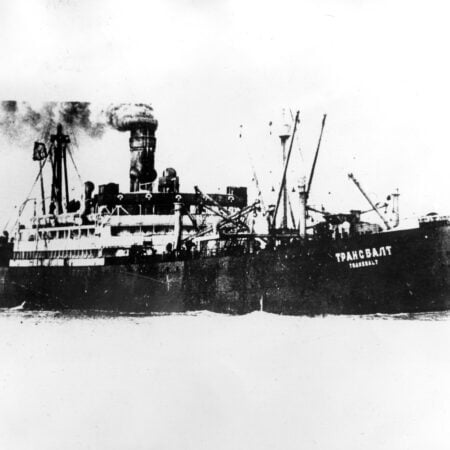

On August 6, 1945, while on a patrol mission, Soviet PK-7 and PK-10 patrol crafts were viciously attacked by two planes in the vicinity of Gavryushkin Kamen island. PK (ПК in Russian) stands for “Pogranichniy Kater”, Пограничный Катер or “Border Patrol Craft”. They had a crew of twelve and armament of 2x 12.7mm MG each (see the photos below). At 09:32, while passing the vicinity of the small island of Gavryushkin Kamen, they were repeatedly attacked by two planes. During the strafing, which continued for the twenty-seven minutes from the mast-top height, 11 sailors died, and another 11 were wounded, including Lt. Cmdr. Nikifor Boyko, commander of the division of Border Patrol boats. PK-7 sustained engine trouble and lost speed. The other craft used the smokescreen and, eventually, towed the damaged PK-7 back to Petropavlovsk. After the war, a monument was erected at the burial place in the territory of the new Border Patrol boat station at Solenoe Lake.

In 1945, my grandfather’s house was next to the boat station by Medvezhye Lake. He and his three sons (including my then-five-year-old father) became good friends with the crews. On the morning of August 6, just as always, some sailors stopped by the house to say hello before embarking on their vessels. As my granddad remembered from talking to the survivors, there was never a doubt that the attacking planes were Japanese. However, some modern Russian reports suggested that the attackers could be the Americans. This prompted me to do some archive digging.

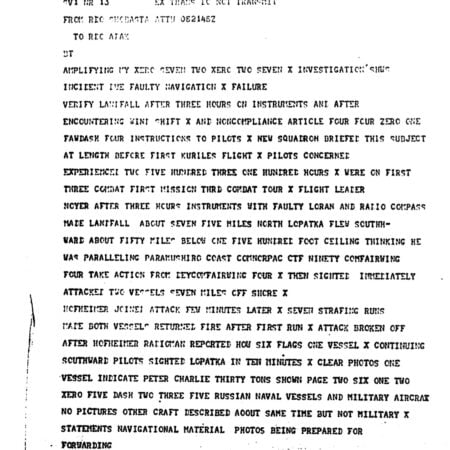

I found a flight report of Lt. Maurice Noyer and Lt. Norman Hofheymer, who were on their first mission to the Kuriles on August 5, Aleutian time. Their newly-formed Squadron VPB-120 had just transferred to Shemya from training at Whidbey Island NAS. With malfunctioning LORAN, they first miscalculated their position by about 70 miles and were spotted and reported by Soviet border guards as “B-24s violating Kamchatka air space near Utashud island”. Then Lt. Noyer in the leading plane (call code 86 Victor, BuNo 59816), thinking they were over Paramushiro coast, failed to make an identifying pass over the Soviet vessels (even though they were briefed to do that) and started a head-on strafing attack. Lt. Hofheimer’s plane (call code 92 Victor, BuNo 59716) joined him shortly, but during the second pass, the top turret gunner noticed the Soviet Navy flags on the boats, and the attack was called off.

Rhodes Arnold, in his book “Foul Weather Front,” quotes the August 5 log book entry of Clyde Paul Cunningham, a gunner on Lt. Noyer’s crew:

“My first strike at the enemy, poor devils didn’t have a chance. Sank one ship, left the other one badly burning. Burnt my gun barrels up. Remember chunks of wood big as car wheels flying off the deck. First run over ship could not fire cause guns wouldn’t bear on target. Second run sank ship with machine gun fire. Second ship was throwing such heavy AA fire at us two runs was all able to make. Saw men on the deck, some dead, some in cold ice water, and some hiding from our accurate fire. Could see large balls of fire coming from the enemy’s five inch guns. I doubt if the second vessel made shore, because the vessel was aflame all over. Heard suddenly over I.E.S. heavy antiaircraft was firing at us from shore. Got out of there in a hurry. Heavy flak was coming up at us all the time, although we were twenty five feet off the water doing 200 miles an hour. One large shell came so close it knocked water over the port wing. We flew so close to the water prop wash was kicking up waves behind us. Did this to keep fighters off our aircraft. Returned to base”.

There was no word about the misidentification, but interesting details were provided about the number of passes, which was officially reported as five, and Soviet AA gun support from the shore.

Unfortunately, Soviet sailors paid the ultimate price for this mistake. Those perished in the attack were:

1. Lt. Cmdr. Boyko Nikifor Ignatyevich, commander of the division of Border Patrol boats, born in 1915.

2. Lt. Tselyutin Viktor Vissarionovich, flagship mechanic of the division of Border Patrol boats, born in 1917, Kropotkin, Krasnodar Territory.

3. PO1c Prikhodko Nikolay Petrovich, boatswain of the PK-7, born in 1913, village of Sheptukhovka, Korneevsky District, Kursk Region.

4. PO2c Andrianov Mikhail Nikolaevich, commander of the gunners’ department of the PK-10, born in 1918.

5. PO2c Tikhonov Pyotr Yakovlevich, helmsman of PK-10, born in 1917, Balakovo, Volsky district, Saratov region, called up in 1941, Perm.

6. PO2c Gavrilkin Sergey Fedorovich, crew member of PK-7 (position not specified), born in 1919.

7. Leading Seaman Krashennikov Vasily Ivanovich, senior gunner of PK-10, born in 1919.

8. Leading Seaman Novoselov Pavel Petrovich, gunner of PK-7, born in 1917, Bezvodnaya village, Kiknursky District, Kirovskaya oblast.

9. Leading Seaman Dubrovny Aleksey Petrovich, gunner of PK-7, born in 1921, Travnoye village, Dovolnensky District, Novosibirsk Region. Heavily wounded on August 6, 1945, died of his wounds on August 12, 1945 in the Petropavlovsk Naval Hospital.

10. Sailor Zimerev Andrey Ivanovich, senior miner of PK-10, born in 1922.

11. Sailor Kalyakin Vasily Ivanovich, hydroacoustic operator of PK-10, born in 1924, Penza Region, Luninsky District, village of Merlinka. Heavily wounded on August 6, 1945, died of his wounds on August 8, 1945 in the Petropavlovsk Naval Hospital.

Surviving sailors showed a wallet of PO2c Sergei Gavrilkin, pierced by a bullet, to my grandfather and his kids. This was one of my late father’s childhood memories.

The deceased sailors were buried in a mass grave on the territory of the base of the 2nd division of border boats of the 60th Order of Lenin Marine Border Detachment of the Primorsky District of the Border Troops of the NKVD of the USSR in Solenoe Ozero Bay in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Since 1968, the name of Lt. Cmdr (Captain 3rd Rank) N.I.Boyko has been borne by the former Solenoe Ozero Street.

Since the monument lists the names of only 8 of the 11 victims – without V.V.Tselyutin, N.P.Prikhodko and P.P.Novosyolov, it can be assumed that the bodies of those three fallen were not delivered to the base in Solenoe Ozero, but during the battle simply fell overboard and, using official wording, were “committed to the sea”.

Why did the surviving sailors insist that the planes were Japanese? They did not want to believe that the Americans could make such a mistake. At that time, the residents of Kamchatka saw with their own eyes the vast volumes of American military and humanitarian aid. Many had the opportunity to communicate and sincerely become friends with the Americans. No one could have imagined then that in just a year or two, the relationship between the two countries would change polarity.

VPB-120 squadron veteran Al Southwick: “I do remember that incident when our planes strafed Soviet ships, but I never learned much about it, because the bombing of Hiroshima took place two days later, and we were all so engrossed in what that meant for us and the world. Incidentally, we had warm feelings for the Soviet military, which suffered such severe losses on the Eastern front. Despite the Cold War, we never forgot those sacrifices. Also they had permitted us to set up a Loran station on the Siberia coast (in fact, those were weather stations in Kamchatka and Primorye Region- BI). That allowed us to navigate with precision, unlike when we were trying to navigate by stars and dead reckoning.“

(from correspondence with the author, 2013).

Seven Soviet freighters and one fishing vessel near Japanese shores perished to American “friendly fire”. As a rule, Soviet vessels underwent American torpedo attacks in bad visibility conditions: in fog or at night.

Following is the list of the Soviet vessels that were lost to American submarines:

Angarstroy — May 1, 1942, East China Sea, to the U.S. submarine SS-210 Grenadier

Kola, Ilmen — February 16 and 17, 1943, Pacific Ocean, SS-276 Sawfish

Seiner #20 — July 9, 1943, Sea of Japan, SS-178 Permit

Belorussia — March 3, 1944, Sea of Okhotsk, SS-381 Sand Lance

Ob— July 6, 1944, Sea of Okhotsk, SS-281 Sunfish

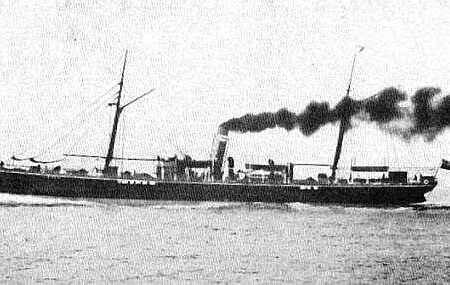

Transbalt— June 13, 1945, Sea of Japan, SS-411 Spadefish

145 of crewmembers and passengers perished from the American torpedo attacks.

October 4, 1943: Liberty-class freighter Odessa was torpedoed on approach to Akhomten Bay at 00:22 a.m. board time by the U.S. submarine S-44. The submarine itself was sank three days later by the Shimushu-class escort ship Ishigaki near Paramushir Island. Odessa, with a large hole at the stern, was towed to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Subsequently the vessel was fully repaired at the ship-repair yard constructed before the war. Odessa was last seen in Golden Horn Bay of Vladivostok as late as 2003, before being cut for scrap.

(Alla Paperno, The Unknown World War Two in the Northern Pacific)